- Home

- Stacy D. Flood

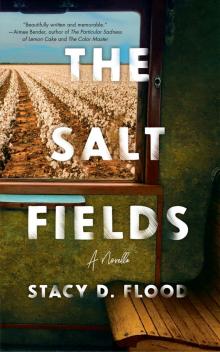

The Salt Fields

The Salt Fields Read online

Praise for The Salt Fields

“There’s a beautiful formality to this writing that beckons a reader in, and then the vibrancy of the dialogue and the surreal allure of the scenes surprise and open up the story. A novella both stamped in time, and timeless. Flood has made something memorable here.”

—Aimee Bender, author of The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake and The Color Master

* * *

“Hyperreal yet hallucinatory, The Salt Fields fits a layered multigenerational saga into the fast-paced jaunt of a novella. A riveting story that mystifies even as more and more is revealed.”

—Siel Ju, author of Cake Time

* * *

“The Salt Fields is a beautiful and powerful novella…with lyrical prose that had me spellbound from the first few sentences. Stacy D. Flood is a remarkable talent, and I can’t wait for the world to know his name.”

—Edan Lepucki, author of Woman No. 17 and California

“Stacy Flood captures the feelings that arise in powerful and precise language, always up to the task. The birds that haunt the landscape and the momentary nuances of light are told as vividly as language can offer. The book is both tragic and beautiful.”

—Maxine Chernoff, author of Here, Camera, Under the Music, and Bop

* * *

“The Salt Fields is a gem—the kind of book you’ll want to underline, dog-ear, study, teach, and beg your friends to read.”

—Christina Clancy, author of

The Second Home and Shoulder Season

* * *

“Stacy Flood’s first novella is a marvel.… The Salt Fields will stay with you long after the last page.”

—Toni Mirosevich, author of Pink Harvest

The Salt Fields

Stacy D. Flood

LANTERNFISH PRESS

Philadelphia

I’M OLD, SO HERE’S WHAT you don’t know yet, and what I don’t want to still remember.

From the time they were born, my father and uncle were taught that everything in the ocean was preserved in salt and everything beyond it was dead or dying or too far away to dream about. Everything on the other side, anything beyond the horizon, had disappeared or floated away distended and wasn’t worth anyone ever remembering. They watched ripples pass along the surface of the water, and beyond these the trees along the mainland shore bent away from the winds.

What they knew of their home, a small island off the coast of South Carolina, was that it was sinking, receding, being devoured ever so slowly. While the men spent their time fishing, my father and uncle would circle the island in the late afternoons. My father became obsessed with sediment, my uncle with flotsam, and together they watched the tides rise and the reeds sink deeper, even against the cutting winds. Others in the town may have noticed this as well, but if so, they never mentioned it—maybe that was their collective secret; every community has one. They simply carried on with their lives as if the encroaching waters weren’t something to be feared—or as if they were tired of fearing things altogether, since there was nowhere left to run. The shores narrowed and more shells were left behind when the waves did recede. The sea was claiming its territory once again.

Fifty years earlier: a slow curl, like a beckoning, which seemed to hover and pause, just for a second, before unfolding into a strike meeting skin. The air condensed and released, pop after pop, snap after snap, as each lash from the whip met flesh in staccato. The man flinched, flexed every muscle beneath each blow, as stripes of blood boiled up fresh atop each wound, and sweat ran down with stinging salt. He dropped to his knees, yet the ropes held him like tentacles, stretching his form between two trees as the air splintered again and again.

The man convulsed, a thin line of spittle hung from his lips, and his breathing thickened. There was a rush in his ears and sweat lined his face, dripping clear salt onto the cooling evening grass beneath him. Through blurred vision he could see his pregnant wife a few yards ahead of him, her mouth open and screaming, her knees digging into the tobacco-stained earth, her whole body angling towards her husband. A few of the older women held her back, leaning with all of their strength to keep her away.

But the strikes continued, blood-tipped lash, scarlet and wet, after blood-tipped lash, until there was little skin left to cut. His breathing slowed; his neck curled forward into his chest.

And his wife screamed: “Just let him die! For God’s sake, just let him die!”

MY GRANDMOTHER WOULD TELL SUCH stories when I was small, to remind me that sometimes survival is relative. Some things we lose should be irreplaceable, and the thorns of the past or the future should always pierce the skin. That night, she said, as those lashes cracked against my grandfather’s back, there was heat in the world but no longer any air. There was no longer oxygen or nitrogen, only heat. On every telling, I wanted to ask her whether my grandfather died that night, but I never did. He died eventually, one way or another—whether as the result of one single incident or the weight of them all together.

Throughout my youth I remember my grandmother being the woman people in town would go to when they wanted something to end. Young women—always with the most tragic of eyes and a tattered but clean shawl around their shoulders—would come to our back porch in the middle of the night. There would be whispers as light escaped the kitchen, and my grandmother would go inside, then return to the doorway with a green glass bottle that she would hand to the lone woman. Even beneath the songs of evening crickets I could only rustle the bed sheets so much without being detected. On the nights I stayed with her, and when those visitors came, I would pretend to be asleep and pull the quilt up over my face, drowning the shadows and sobs which darted across the night. I never really outgrew the comfort of that quilt. Years later, when I went off to college, it was the one possession that I was determined not to leave behind.

Without fail, a few days after a woman’s visit, the people in the town would talk about how that very woman had, tragically, lost something nights earlier. I would often see those women’s faces in the congregation the following Sundays, and they never looked happy, though some looked grateful or relieved. Some of them I never saw again. Mostly it was the darker-skinned women of the town who came to see my grandmother late at night. Unlike the lighter-skinned women, these darker ones sat in church alone, searching the crowd with lonesome eyes for some Biblical kindness, or they sat with their gaze cast downward—not in prayer, but as if they longed for something they knew they would never see in this lifetime, at least not with bodily eyes.

It made sense. Because who in their proper mind would want to bring a child into this world, raise him from wind and dust into this horror, only to be lesser than?

My grandmother had one daughter. On an island across the water there were two brothers, orphans, who were raised hard. Long hours of schooling, and beatings in order to release from their minds and from their blood any remnants of the curse into which they were born. The boys were objects, equipment, tools, insects, nobody’s children, and many nights they would sneak away from the family that kept them and sleep clutching one another in a stranger’s boat, whichever vessel had the heaviest tarp, as the winds roared above them and the waters below cracked, swayed, sizzled, and hissed. As they grew older they shivered less and less. On warmer days, when all you could smell was the sea, the two would sit side by side on the beach, blinded by the reflections from the waves, and watch the distant shore.

Until one afternoon the birds left. The fish jumped less. Dark clouds raced in to cover the sun and hide the moon. The boys measured the rushing winds and prepared themselves. My father packed a few books. My uncle slipped through the town taking a

s much money and canned food as he could steal and carry away in two pillow cases. Then, in the small hours of the morning, they pushed a boat into the water.

Once the brothers were drifting out from the shore, the sea rose further; the rains surged and slashed sideways, and lanterns were lit as the island’s fishermen met the rush of water onto the streets and into their homes. My father could see chaos unfolding through the windows of the kitchens, where firelight flashed off streams of rain, but there were no other boats being prepared or launched. The men came down to stand on the shore, some pointing towards the boat the brothers sailed in, but found themselves marooned there as the sea grew higher and higher.

My father couldn’t hear any shouts or screams over the storm winds. Even when he turned to my uncle to ask a question, his words were ripped away, unheard, by the tumultuous air. My uncle stared stone-faced toward the distant shore they’d dreamed about their entire lives. My father returned his gaze to the island they’d left behind. The men on the shore were raising their lanterns higher, the women tightly clutching children and babies. In the patches of dim light he could also see the splintered pieces of other boats swirling on the waves—crushed and compacted by the storm, irretrievable.

While searching for food and money, my uncle had released every other boat on the island into the sea, which left each resident besides himself and his brother stranded: a dozen families left to drown in the enveloping night. Even through the distance and the drops of rain heavy on his eyelashes, my father could still see their tears.

As the brothers sailed farther away the lights dimmed behind them and brightened ahead. Jellyfish wide as dinner plates floated in the night waters beneath the small boat. My father turned away from his island one last time, never to look back.

Once the storm had broken, my uncle pronounced as he rowed: “They didn’t love us, so we had to do this, you understand?” When my father didn’t reply, he added—to convince himself and his own soul as well as my father: “If we didn’t we would have drowned along with them, one day, one way or another.”

* * *

The few townspeople who woke early that next morning saw my rain-soaked father wander up the main road. No one asked questions, as if no one had any right to. And as the town stared at him and his wet-pillowcase traveling bag, he walked into a small crawfish diner. There he asked if anyone was taking boarders and was at last taken in by a lonely couple glad to have a young man in their home to help with the chores, even one who had seemed to emerge from the sea like treasure.

He was alone. He and my uncle had agreed to part ways for fear their actions would be discovered. Even years later, my father claimed that he still thought of his brother every time the rain fell like daggers and exploded in puddles along the dirt roads.

They had split the stolen money evenly. My father kept his share hidden in a hollowed-out almanac that he read each night, since he would spend the remainder of his childhood mysterious and alone. Once older, he rented a tiny room in a boarding house one state away, which was the boarding house that my grandmother owned.

He grew up athletic, handsome, and God-fearing to a degree that no one could fully understand. Plus, he had money; no one questioned from where. My mother fell in love with him. They eventually married, bore one child, and then purchased one of the town’s general stores.

Of his lost brother, my father heard distant stories: the young drifter with money and some talent with a pocketknife. They had promised to stay in touch as best they could, but fewer and fewer letters found their way back as the years moved forward. The last my father knew was that my uncle had headed farther west, reaching St. Louis before drinking up most of his share of loot. There he fell in love with a dancing girl, the daughter of an escaped slave, and the two of them headed to the left side of the continent, reaching Wyoming before the drinking got the best of them both. His wife died from winters when too much of the money went into shot glasses rather than firewood; from what my father heard, it was the type of cold that seeps into the bones so deeply that you can’t get rid of it. She had left my uncle and moved into a boarding house a few weeks before it finally took her life. That was her triumph. Afterwards, my uncle traveled with the children of runaway slaves who had become cowboys since they were raised breaking horses. My uncle became something of an oil man and cowboy himself until the money was gone again and his bones became brittle and weary, and he was left to ride fence on an old horse, day after day, into the winter pastures where not a single blade of grass could reach through the thick, sharp snow.

My father always wondered if his brother had any children, and every time the door to his store would swing open and a dark-faced stranger would walk in, my father thought of the possibility that this was the niece or nephew he longed for, one loaded with stories of my uncle’s well-being. When that new customer simply ordered a can of baking soda or condensed milk instead, my father always looked dejected, which made the town believe that he was generally more morose than he truly was. My father sent news westward along with any traveler he could find, anyone who was heading towards those mountains he’d only read about in magazines. He wanted to tell my uncle that all was forgiven, that no one had followed them from the island, and that there was a job at the general store if he wanted it. My father was convinced that word would reach his only brother eventually. It had to; that’s how the world worked. You sent out what you expected from it, with enough heart and longing, and your reward came back to you. My father believed that. He had to.

Yet he used to dream every night of his brother’s death through various tragedies—a tree falling on him, the earth beneath his feet simply giving way, a bullet shot through his temple as he lay sleeping against the cold earth. And after many years, on his own deathbed, with his eyes clouded and the fever winning, my father called out for his brother.

“Is he here? Is he dead yet?”

Everyone else around him thought that he was referring to me. I knew better.

But people also said that I’d gotten my wanderlust from this uncle I’d never met, even though I wouldn’t say I had a lust for travel, rather an inner knowledge that I certainly didn’t belong where I was. Throughout my childhood I was content, if not really happy; the latter seemed too much to ask for through the long hot days and sweltering nights. I had food, clothing, and friends with whom I shared marbles and tin toy cars, but I was the wealthiest, and it kept my friends distant. Best friends came, then moved away, and of the friends who remained, their parents remembered my father’s mysterious arrival and my grandmother’s mysterious late-night occupation—too well for them to allow their offspring to spend too much time with me. I understood and was content to keep mostly to myself. I think this saddened my mother a little, and to try to lighten my demeanor, my father would regale me with fantastic stories of his journey to our larger shore. I never believed in magic and wonder, so the tales were rarely successful; they only served as a reminder of his trials, real or imagined, versus my relative comfort.

As a young man I worked in my father’s store, saved up my wages, and, since I never found anything else interesting enough to apply myself to, devoted my time to school, and eventually my money to college. I attended Morehouse, then transferred to Tuskegee, where I fell in love time and again—never deeply enough to hold my interest for very long. I wanted to be a physician—not a seeds-and-roots doctor like my grandmother but someone versed in all the interconnected systems of the body. When the money for my education dried up, however, faster than expected, I returned home to become a teacher and to marry a sweetheart I’d found more and more interesting as our summer friendships grew. We held hands, danced, shared Coca Cola and saltwater taffy on warm evenings, and held our first kiss for so long that time itself faded.

She broke it first and moved farther and farther away over the years, always accusing me of only seeing the edges of things, never the center or the whole or the heart. We had

a daughter. Being an only child myself, I inherited the old family home after my mother passed. But when my daughter was three, my wife left us for another man, someone I hoped she’d found true love with. I understood: she had grown while I had not, and when I think of her leaving I imagine the two of us standing at the edge of a cliff, her growing wings and soaring into the sky while I stand on the edge, on my toes, watching, afraid to stretch any higher.

I think of her soaring and then I watch her fall. She was murdered later that summer, stabbed with a knife twenty-seven times. There were no suspects—not even the man she flew away with, who disappeared the day her body was found beneath crumpled bed sheets soaked with blood—and no investigation. This was the age when the murder of a Black woman didn’t warrant the pay, ink, or gasoline that it would take to investigate, especially should the evidence lead to anyone other than a Black man. So the case simply got colder and colder, then frozen, until it drifted away like snow before her body was even buried.

* * *

“The Lord moves in mysterious ways,” they told me, as their weathered, gnarled hands drifted from my shoulder to my tricep to my elbow, then away.

And for a year and a half after my wife died, my daughter and I were alone. Existing in that house through the seasons, she and I were pleasant enough to each other but never friends, or close. We worked the land together sometimes; she picked flowers rather than the weeds I asked her to, since she claimed that weeds were just wildflowers nobody loved yet. Her smile reminded me of her mother’s too much and too often, so in return I smiled less, and by extension discouraged my daughter from smiling at all. We ate our meals mostly in silence, the whispering of the breeze louder than our words, and when the breezes turned into the cold winter winds, the crackling of the fire was the loudest sound in our house. We completed our chores dutifully. I never yelled at her, nor she at me. I listened to her sobs at night; she listened to me turn the pages of books I’d already read. We prayed, said what we were thankful for, and waited for something to break.

The Salt Fields

The Salt Fields